Learning Node Moving to the Server-Side (Powers Shelley.) (Z-Library)¶

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

finish packet (FIN), that is sent by a socket to signal that the transmission is done.

Think of two people talking by walkie-talkie. The walki-talkies are the end-points, the sockets of the communication. When two or more people want to speak to each other, they have to tune into the same radio frequency. Then when one person wants to communicate with the other, they push a button on the walki-talkie, and connect to the appropriate person using some form of identification. They also use the word “over” to signal that they’re no longer talking, but listening, instead. The other person pushes the talk button on their walkie-talkie, acknowledges the communication, and again using “over” to sig-nal they’re in listening mode.

The communication continues until one person signals “over and out”, that the communication is finished. Only one person can talk at a time. Walkie-talkie communication streams are known as half-duplex , because communication can only occur in one direction at a time. *Full-duplex communication streams al-*lows two-way communication.

We’ve already worked with half and full-duplex streams, in Chapter 6. The streams used to write to, and read from, files were examples of half-duplex streams: the streams supported either the readable interface, or the writable interface, but not both at the same time. The zlib compression stream is an ex-ample of a full-duplex stream, allowing simultaneous reading and writing. The same applies to networked streams (TCP), as well as encrypted (Crypto). We’ll look at Crypto later in the chapter, but first, we’ll dive into TCP.

TCP Sockets and Servers

TCP provides the communication platform for most Internet applications, such as web service and email. It provides a way of reliably transmitting data be-tween client and server sockets. TCP provides the infrastructure on which the application layer, such as HTTP, resides.

We can create a TCP server and client, just as we did the HTTP ones. Creat-ing the TCP server is a little diferent than creating an HTTP server. Rather than passing a requestListener to the server creation function, with its separate response and request objects, the TCP callback function’s sole argument is an instance of a socket that can both send, and receive.

To better demonstrate how TCP works, Example 7-1 contains the code to create a TCP server. Once the server socket is created, it listens for two events: when data is received and when the client closes the connection. It then prints out the data it received to the console, and repeats the data back to the client.

The TCP server also attaches an event handler for both the listening event and an error . In previous chapters, I just plopped a console.log() message afer the server is created, following pretty standard practice in Node.

Servers, Streams, and Sockets

However, since the listen() event is asynchronous, technically this practice is incorrect. Instead, you can incorporate a message in the callback function for the listen function, or you can do what I’m doing here, which is attach an event handler to the listening event, and correctly providing feedback.

In addition, I’m also providing more sophisticated error handling, modeled afer that in the Node documentation. The application is processing an error event, and if the error is because the port is currently in use, it waits a small amount of time, and tries again. For other errors—such as accessing a port like 80, which requires special privileges—the full error message is printed out to the console.

EXAMPLE 7-1. A simple TCP server, with a socket listening for client communication on port 8124

var net = require('net');

const PORT = 8124;

var server = net.createServer(function(conn) {

console.log('connected');

conn.on('data', function (data) {

console.log(data + ' from ' + conn.remoteAddress + ' ' + conn.remotePort);

conn.write('Repeating: ' + data);

});

conn.on('close', function() {

console.log('client closed connection');

});

}).listen(PORT);

server.on('listening', function() {

console.log('listening on ' + PORT);

});

server.on('error', function(err){

if (err.code == 'EADDRINUSE') {

console.warn('Address in use, retrying...');

setTimeout(() => {

server.close();

server.listen(PORT);

}, 1000);

}

else {

console.error(err);

}

});

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

To test the server you can use a TCP client application such as the netcat utility (nc) in Linux or the Mac OS, or an equivalent Windows application. Using netcat, the following connects to the server application at port 8124, writing data from a text file to the server:

nc burningbird.net 8124 < mydata.txt

In Windows, there are TCP tools, such as SocketTest , you can use. You can pass in an optional parameters object, consisting of two values:

pauseOnConnect and allowHalfOpen , when creating the socket. The default value for both is false :

{ allowHalfOpen: false,

pauseOnConnect: false }

Setting allowHalfOpen to true instructs the socket not to send a FIN when it receives a FIN packet from the client. Doing this keeps the socket open for writ-ing (not reading). To close the socket, you must use the end() function. Setting pauseOnConnect to true allows the connection to be passed, but no data is read. To begin reading data, call the resume() method on the socket.

Rather than using a tool to test the server, you can create your own TCP cli-ent application. The TCP client is just as simple to create as the server, as shown in Example 7-2 . The call to setEncoding() on the client changes the encoding for the received data. The data is transmitted as a bufer, but we can use setEncoding() to read it as a utf8 string. The socket’s write() method is used to transmit the data. It also attaches listener functions to two events: data , for received data, and close , in case the server closes the connection. EXAMPLE 7-2. The client socket sending data to the TCP server

var net = require('net');

var client = new net.Socket();

client.setEncoding('utf8');

// connect to server

client.connect ('8124','localhost', function () {

console.log('connected to server');

client.write('Who needs a browser to communicate?');

});

// when receive data, send to server

process.stdin.on('data', function (data) {

client.write(data);

});

Servers, Streams, and Sockets

// when receive data back, print to console

client.on('data',function(data) {

console.log(data);

});

// when server closed

client.on('close',function() {

console.log('connection is closed');

});

The data being transmitted between the two sockets is typed in at the termi-nal, and transmitted when you press Enter. The client application sends the text you type, and the TCP server writes out to the console when it receives it. The server repeats the message back to the client, which in turn writes the message out to the console. The server also prints out the IP address and port for the client using the socket’s remoteAddress and remotePort properties. Follow-ing is the console output for the server afer several strings were sent from the client:

Hey, hey, hey, hey-now.

from ::ffff:127.0.0.1 57251

Don't be mean, we don't have to be mean.

from ::ffff:127.0.0.1 57251

Cuz remember, no matter where you go,

from ::ffff:127.0.0.1 57251

there you are.

from ::ffff:127.0.0.1 57251

The connection between the client and server is maintained until you kill one or the other using Ctrl-C. Whichever socket is still open receives a close event that’s printed out to the console. The server can also serve more than one connection from more than one client, since all the relevant functions are asyn-chronous.

I P V 4 M A P P E D T O I P V 6 A D D R E S S E S

The sample output from running the client/server TCP applications in this section demonstrate an IPv4 address mapped to IPv6, with the addi-tion of : :ffff .

As I mentioned earlier, TCP is the underlying transport mechanism for much of the communication functionality we use on the Internet today, including HTTP. Which means that, instead of binding to a port with an HTTP server, we can bind directly to a socket.

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

To demonstrate, I modified the TCP server from the earlier examples, but in-stead of binding to a port, the new server binds to a Unix socket, as shown in Example 7-3 . I also had to modify the error handling to unlink the Unix socket if the application is restarted, and the socket is already in use. In a production en-vironment, you’d want to make sure no other clients are using the socket be-fore you would do something so abrupt.

EXAMPLE 7-3. TCP server bound to a Unix socket

var net = require('net');

var fs = require('fs');

const unixsocket = '/home/examples/public_html/nodesocket'; var server = net.createServer(function(conn) {

console.log('connected');

conn.on('data', function (data) {

conn.write('Repeating: ' + data);

});

conn.on('close', function() {

console.log('client closed connection');

});

}).listen(unixsocket);

server.on('listening', function() {

console.log('listening on ' + unixsocket);

});

// if exit and restart server, must unlink socket

server.on('error',function(err) {

if (err.code == 'EADDRINUSE') {

fs.unlink(unixsocket, function() {

server.listen(unixsocket);

});

} else {

console.log(err);

}

});

process.on('uncaughtException', function (err) {

console.log(err);

});

C H E C K I F A N O T H E R I N S T A N C E O F T H E S E R V E R I S R U N N I N G

Before unlinking the socket, you can check to see if another instance of the server is running. A solution at Stack Overflow provides an alterna-tive clean up technique accounting for this situation.

The client application is shown in Example 7-4 . It’s not that much diferent than the earlier client that communicated with the port. The only diference is adjusting for the connection point.

EXAMPLE 7-4. Connecting to the Unix socket and printing out received data var net = require('net');

var client = new net.Socket();

client.setEncoding('utf8');

// connect to server

client.connect ('/home/examples/public_html/nodesocket', function () { console.log('connected to server');

client.write('Who needs a browser to communicate?');

});

// when receive data, send to server

process.stdin.on('data', function (data) {

client.write(data);

});

// when receive data back, print to console

client.on('data',function(data) {

console.log(data);

});

// when server closed

client.on('close',function() {

console.log('connection is closed');

});

??? covers the SSL version of HTTP, HTTPS , along with Crypto and TLS/ SSL.

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

UDP/Datagram Socket

TCP requires a dedicated connection between the two endpoints of the com-munication. UDP is a connectionless protocol, which means there’s no guaran-tee of a connection between the two endpoints. For this reason, UDP is less reli-able and robust than TCP. On the other hand, UDP is generally faster than TCP, which makes it more popular for real-time uses, as well as technologies such as VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol), where the TCP connection requirements could adversely impact the quality of the signal.

Node core supports both types of sockets. In the last section, I demonstrated the TCP functionality. Now, it’s UDP’s turn.

The UDP module identifier is dgram :

require ('dgram');

To create a UDP socket, use the createSocket method, passing in the type of socket—either udp4 or udp6 . You can also pass in a callback function to listen for events. Unlike messages sent with TCP, messages sent using UDP must be sent as bufers, not strings.

Example 7-5 contains the code for a demonstration UDP client. In it, data is accessed via process.stdin , and then sent, as is, via the UDP socket. Note that we don’t have to set the encoding for the string, since the UDP socket ac-cepts only a bufer and the process.stdin data is a bufer. We do, however, have to convert the bufer to a string, using the bufer’s toString method, in order to get a meaningful string for the console.log method call that echoes the input.

EXAMPLE 7-5. A datagram client that sends messages typed into the terminal var dgram = require('dgram');

var client = dgram.createSocket("udp4");

process.stdin.on('data', function (data) {

console.log(data.toString('utf8'));

client.send(data, 0, data.length, 8124, "examples.burningbird.net", function (err, bytes) {

if (err)

console.error('error: ' + err);

else

console.log('successful');

});

});

Guards at the Gate

The UDP server, shown in Example 7-6 , is even simpler than the client. All the server application does is create the socket, bind it to a specific port (8124), and listen for the message event. When a message arrives, the application prints it out using console.log , along with the IP address and port of the sender. No encoding is necessary to print out the message—it’s automatically converted from a bufer to a string.

We didn’t have to bind the socket to a port. However, without the binding, the socket would attempt to listen in on every port.

EXAMPLE 7-6. A UDP socket server, bound to port 8124, listening for messages var dgram = require('dgram');

var server = dgram.createSocket("udp4");

server.on ("message", function(msg, rinfo) {

console.log("Message: " + msg + " from " + rinfo.address + ":" + rinfo.port);

});

server.bind(8124);

I didn’t call the close method on either the client or the server afer send-ing/receiving the message. However, no connection is being maintained be-tween the client and server—just the sockets capable of sending a message and receiving communication.

Guards at the Gate

Security in web applications goes beyond ensuring that people don’t have ac-cess to the application server. Security can be complex, and even a little intimi-dating. Luckily, when it comes to Node applications, several of the components we need for security have already been created. We just need to plug them in, in the right place and at the right time.

Setting Up TLS/SSL

Secure, tamper-resistant communication between a client and a server occurs over SSL (Secure Sockets Layer), and its upgrade, TLS (Transport Layer Securi-ty). TLS/SSL provides the underlying encryption for HTTPS, which I cover in the next section. However, before we can develop for HTTPS, we have to do some environment setup.

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

A TLS/SSL connection requires a handshake between client and server. Dur-*ing the handshake, the client (typically a browser) lets the server know what kind of security functions it supports. The server picks a function and then sends through an *SSL certificate , which includes a public key. The client con-firms the certificate and generates a random number using the server’s key, sending it back to the server. The server then uses its private key to decrypt the number, which in turn is used to enable the secure communication.

For all this to work, you’ll need to generate both the public and private key, as well as the certificate. For a production system, the certificate would be sign-ed by a trusted authority , such as our domain registrars, but for development purposes you can make use of a self-signed certificate . Doing so generates a rather significant warning in the browser, but since the development site isn’t being accessed by users, there won’t be an issue.

P R E V E N T I N G S E L F - S I G N E D C E R T I F I C A T E W A R N I N G S

If you’re using a self-signed certificate, you can avoid browser warnings if you access the Node application via localhost (i.e. https://localhost:

8124). You can also avoid using self-signed certificates without the cost of a commercial signing authority by using Lets Encrypt , currently in open beta. The site provides documentation for setting up the certifi-cate.

The tool used to generate the necessary files is OpenSSL. If you’re using Li-nux, it should already be installed; there’s a binary installation for Windows, and Apple is pursuing its own Crypto library. In this section, I’m just covering setting up a Linux environment.

To start, type the following at the command line:

openssl genrsa -des3 -out site.key 1024

The command generates the private key, encrypted with Triple-DES and stored in PEM (privacy-enhanced mail) format, making it ASCII readable.

You’ll be prompted for a password, and you’ll need it for the next task, creat-ing a certificate-signing request (CSR).

When generating the CSR, you’ll be prompted for the password you just cre-ated. You’ll also be asked a lot of questions, including the country designation (such as US for United States), your state or province, city name, company name and organization, and email address. The question of most importance is the one asking for the Common Name. This is asking for the hostname of the site—for example, burningbird.net or yourcompany.com . Provide the hostname where the application is being served. In my example code, I created a certifi-cate for examples.burningbird.net .

Guards at the Gate

openssl req -new -key site.key -out site.csr

The private key wants a passphrase . The problem is, every time you start up the server you’ll have to provide this passphrase, which is an issue in a produc-tion system. In the next step, you’ll remove the passphrase from the key. First, rename the key:

mv site.key site.key.org

Then type:

openssl rsa -in site.key.org -out site.key

If you do remove the passphrase, make sure your server is secure by ensur-ing that the file is readable only by root.

The next task is to generate the self-signed certificate. The following com-mand creates one that’s good only for 365 days:

openssl x509 -req -days 365 -in site.csr -signkey site.key -out final.crt Now you have all the components you need in order to use TLS/SSL and

HTTPS.

Working with HTTPS

Web pages that ask for user login or credit card information had better be served as HTTPS, or we should give the site a pass. HTTPS is a variation of the HTTP protocol, except that it’s also combined with SSL to ensure that the web-site is who and what we think it is, that the data is encrypted during transit, and the data arrives intact and without any tampering.

Adding support for HTTPS is similar to adding support for HTTP, with the ad-dition of an options object that provides the public encryption key, and the signed certificate. The default port for an HTTPS server difers, too: HTTP is served via port 80 by default, while HTTPS is served via port 443.

A V O I D I N G T H E P O R T N U M B E R

One advantage to using SSL with your Node application is the default port for HTTPS is 443, which means you don’t have to specify the port number when accessing the application, and not conflict with your Apache or other web server. Unless you’re also utilizing HTTPS with your non-Node web server, of course.

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

Example 7-7 demonstrates a very basic HTTPS server. It does little beyond sending a variation of our traditional Hello, World message to the browser. EXAMPLE 7-7. Creating a very simple HTTPS server

var fs = require("fs"),

https = require("https");

var privateKey = fs.readFileSync('site.key').toString(); var certificate = fs.readFileSync('final.crt').toString(); var options = {

key: privateKey,

cert: certificate

};

https.createServer(options, function(req,res) {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end("Hello Secure World\n");

}).listen(443);

The public key and certificate are opened, and their contents are read syn-chronously. The data is attached to the options object, passed as the first pa-rameter in the https.createServer method. The callback function for the same method is the one we’re used to, with the server request and response object passed as parameters.

When you run the Node application, you’ll need to do so with root permis-sions. That’s because the server is running bound to the default of port 443. Binding to any port less than 1024 requires root privilege. You can run it using another port, such as 3000, and it works fine, except when you access the site, you’ll need to use the port:

https://examples.burningbird.net:3000

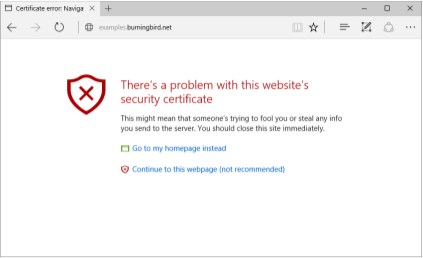

Accessing the page demonstrates what happens when we use a self-signed certificate, as shown in Figure 7-1 . It’s easy to see why a self-signed certificate should be used only during testing. Accessing the page using localhost also dis-ables the security warning.

FIGURE 7-1

What happens when

you use Edge to

access a website

using HTTPS with a

self-signed

certifcate

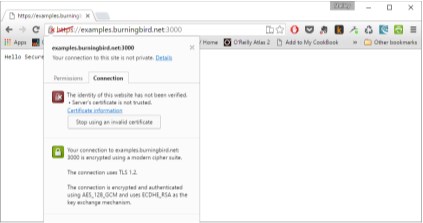

The browser address bar demonstrates another way that the browser sig-nals that the site’s certificate can’t be trusted, as shown in Figure 7-2 . Rather than displaying a lock indicating that the site is being accessed via HTTPS, it displays a lock with a red *x showing that the certificate can’t be trusted. Click-*ing the icon opens an information window with more details about the certifi-cate.

FIGURE 7-2

More information

about the certifcate

is displayed when

the lock icon is

clicked, as

demonstrated in

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

Encrypting communication isn’t the only time we use encryption in a web application. We also use it to store user passwords and other sensitive data. The Crypto Module

Node provides a module used for encryption, Crypto, which is an interface for OpenSSL functionality. This includes wrappers for OpenSSL’s hash, HMAC, ci-pher, decipher, sign, and verify functions. The Node component of the technol-ogy is actually rather simple to use but there is a strong underlying assumption that the Node developer knows and understands OpenSSL and what all the var-ious functions are.

B E C O M E F A M I L I A R W I T H O P E N S S L

I cannot recommend strongly enough that you spend time becoming fa-miliar with OpenSSL before working with Node’s Crypto module. You can explore OpenSSL’s documentation , and you can also access a free book on OpenSSL, OpenSSL Cookbook , by Ivan Risti ć .

I’m covering a relatively straight-forward use of the Crypto module to en-cyrpt a password that’s stored in a database, using OpenSSL’s hash functionali-ty. The same type of functionality can also be used to create a hash for use as a checksum , to ensure that data that’s stored or transmitted hasn’t been corrup-ted in the process.

M Y S Q L

The example in this section makes use of MySQL. For more information on the node-myself module used in this section, see the module’s Git-hub repository . If you don’t have access to MySQL, you can store the username, password, and salt in a local file, and modify the example ac-cordingly.

One of the most common tasks a web application has to support is also one of the most vulnerable: storing a user’s login information, including password. It probably only took five minutes afer the first username and password were stored in plain text in a web application database before someone came along, cracked the site, got the login information, and had his merry way with it.

You do not store passwords in plain text. Luckily, you don’t need to store passwords in plain text with Node’s Crypto module.

You can use the Crypto module’s createHash method to encrypt the pass-word. An example is the following, which creates the hash using the sha1 algo-

Guards at the Gate

rithm, uses the hash to encode a password, and then extracts the digest of the encrypted data to store in the database:

var hashpassword = crypto.createHash('sha1')

.update(password)

.digest('hex');

The digest encoding is set to hexadecimal. By default, encoding is binary, and base64 can also be used.

Many applications use a hash for this purpose. However, there’s a problem with storing plain hashed passwords in a database, a problem that goes by the innocuous name of rainbow table .

Put simply, a rainbow table is basically a table of precomputed hash values for every possible combination of characters. So, even if you have a password that you’re sure can’t be cracked—and let’s be honest, most of us rarely do— chances are, the sequence of characters has a place somewhere in a rainbow table, which makes it much simpler to determine what your password is.

The way around the rainbow table is with *salt (no, not the crystalline varie-*ty), a unique generated value that is concatenated to the password before en-cryption. It can be a single value that is used with all the passwords and stored securely on the server. A better option, though, is to generate a unique salt for each user password, and then store it with the password. True, the salt can also be stolen at the same time as the password, but it would still require the person attempting to crack the password to generate a rainbow table specifically for the one and only password—adding immensely to the complexity of cracking any individual password.

Example 7-8 is a simple application that takes a username and a password passed as command-line arguments, encrypts the password, and then stores both as a new user in a MySQL database table. I’m using MySQL rather than any other database because it is ubiquitous on most systems, and a system with which most people are familiar.

To follow along with the example, use the node-mysql module by installing it as follows:

npm install node-mysql

The table is created with the following SQL:

CREATE TABLE user (userid INT NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT, PRIMARY KEY(userid), username VARCHAR(400) NOT NULL, password VARCHAR(400) NOT NULL, salt DOUBLE NOT NULL );

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

The salt consists of a date value multiplied by a random number and roun-ded. It’s concatenated to the password before the resulting string is encrypted. All the user data is then inserted into the MySQL user table.

EXAMPLE 7-8. Using Crypto’s createHash method and a salt to encrypt a password var mysql = require('mysql'),

crypto = require('crypto');

var connection = mysql.createConnection({

host: 'localhost',

user: 'username',

password: 'userpass'

});

connection.connect();

connection.query('USE nodedatabase');

var username = process.argv[2];

var password = process.argv[3];

var salt = Math.round((new Date().valueOf() * Math.random())) + ''; var hashpassword = crypto.createHash('sha512')

.update(salt + password, 'utf8')

.digest('hex');

// create user record

connection.query('INSERT INTO user ' +

'SET username = ?, password = ?, salt = ?

[username, hashpassword, salt], function(err, result) { if (err) console.error(err);

connection.end();

});

Following the code from the top, first a connection is established with the database. Next, the database with the newly created table is selection. The username and password are pulled in from the command line, and then the crypto magic begins.

The salt is generated, and passed into the function to create the the hash, using the sha512 algorithm. Functions to update the password with the salt, and set the hash encoding are chained to the function to create the hash. The newly encrypted password is then inserted into the newly created table, along with the username.

The application to test a username and password, shown in Example 7-9 , queries the database for the password and salt based on the username. It uses the salt to, again, encrypt the password. Once the password has been encryp-

Guards at the Gate

ted, it’s compared to the password stored in the database. If the two don’t match, the user isn’t validated. If they match, then the user’s in.

EXAMPLE 7-9. Checking a username and a password that has been encrypted var mysql = require('mysql'),

crypto = require('crypto');

var connection = mysql.createConnection({

user: 'username',

password: 'userpass'

});

connection.query('USE nodedatabase');

var username = process.argv[2];

var password = process.argv[3];

connection.query('SELECT password, salt FROM user WHERE username = ?', [username], function(err, result, fields) {

if (err) return console.log(err);

var newhash = crypto.createHash('sha512')

.update(result[0].salt + password, 'utf8')

.digest('hex');

if (result[0].password === newhash) {

console.log("OK, you're cool");

} else {

console.log("Your password is wrong. Try again.");

}

connection.end();

});

Trying out the applications, we first pass in a username of Michael , with a password of apple*frk13* :

node password.js Michael apple*frk13*

We then check the same username and password:

node check.js Michael apple*frk13*

and get back the expected result:

OK, you're cool

Trying it again, but with a diferent password:

CHAPTER 7: Networking, Sockets, and Security

node check.js Michael badstuff

we get back the expected result again:

Your password is wrong. Try again

The crypto has can also be used in a stream. As an example, consider a checksum, which is an algorithmic way of determining if data has transmitted successfully. You can create a hash of the file, and pass this along with the file when transmitting it. The person who downloads the file can then use the hash to verify the accuracy of the transmission. The following code uses the pipe() function and the duplex nature of the Crypto functions to create such a hash.

var crypto = require('crypto');

var fs = require('fs');

var hash = crypto.createHash('sha256');

hash.setEncoding('hex');

var input = fs.createReadStream('main.txt');

var output = fs.createWriteStream('mainhash.txt');

input.pipe(hash).pipe(output);

You can also use md5 as the algorithm in order to generate a MD5 checksum, which has popular support in most environments.

var hash = crypto.createHash('md5');

Child Processes 8

Operating systems provide access to a great deal of functionality, but much of it is only accessible via the command line. It would be nice to be able to access this functionality from a Node application. That’s where child processes come in.

Node enables us to run a system command within a new child process, and listen in on its input/output. This includes being able to pass arguments to the command, and even pipe the results of one command to another. The next sev-eral sections explore this functionality in more detail.

All but the last example demonstrated in this chapter use Unix com-mands. They work on a Linux system, and should work in a Mac. They won’t, however, work in a Windows Command window.

child_process.spawn

There are four diferent techniques you can use to create a child process. The most common one is using the spawn method. This launches a command in a new process, passing in any arguments. In the following, we create a child pro-cess to call the Unix pwd command to print the current directory. The command takes no arguments:

var spawn = require('child_process').spawn,

pwd = spawn('pwd');

pwd.stdout.on('data', function (data) {

console.log('stdout: ' + data);

});

pwd.stderr.on('data', function (data) {

console.log('stderr: ' + data);

});

CHAPTER 8: Child Processes

pwd.on('close', function (code) {

console.log('child process exited with code ' + code); });

Notice the events that are captured on the child process’s stdout and stderr . If no error occurs, any output from the command is transmitted to the child process’s stdout , triggering a data event on the process. If an error oc-curs, such as in the following where we’re passing an invalid option to the com-mand:

var spawn = require('child_process').spawn,

pwd = spawn('pwd', ['-g']);

Then the error gets sent to stderr , which prints out the error to the console: stderr: pwd: invalid option -- 'g'

Try `pwd --help' for more information.

child process exited with code 1

The process exited with a code of 1 , which signifies that an error occurred. The exit code varies depending on the operating system and error. When no er-ror occurs, the child process exits with a code of 0 .

L I N E B U F F E R I N G

The Node documentation has issued a warning that some programs use line-buffered I/O internally. This could result in the data being sent to the program not being immediately consumed.

The earlier code demonstrated sending output to the child process’s stdout and stderr , but what about stdin ? The Node documentation for child pro-cesses includes an example of directing data to stdin . It’s used to emulate a Unix pipe (|) whereby the result of one command is immediately directed as in-put to another command. I adapted the example in order to demonstrate one of my favorite uses of the Unix pipe—being able to look through all subdirecto-ries, starting in the local directory, for a file with a specific word (in this case, test ) in its name:

find . -ls | grep test

Example 8-1 implements this functionality as child processes. Note that the first command, which performs the find , takes two arguments, while the sec-ond one takes just one: a term passed in via user input from stdin . Also note

child_process.spawn

that, unlike the example in the Node documentation, the grep child process’s stdout encoding is changed via setEncoding . Otherwise, when the data is printed out, it would be printed out as a bufer.

EXAMPLE 8-1. Using child processes to fnd fles in subdirectories with a given search term, “test”

var spawn = require('child_process').spawn,

find = spawn('find',['.','-ls']),

grep = spawn('grep',['test']);

grep.stdout.setEncoding('utf8');

// direct results of find to grep

find.stdout.on('data', function(data) {

grep.stdin.write(data);

});

// now run grep and output results

grep.stdout.on('data', function (data) {

console.log(data);

});

// error handling for both

find.stderr.on('data', function (data) {

console.log('grep stderr: ' + data);

});

grep.stderr.on('data', function (data) {

console.log('grep stderr: ' + data);

});

// and exit handling for both

find.on('close', function (code) {

if (code !== 0) {

console.log('find process exited with code ' + code); }

// go ahead and end grep process

grep.stdin.end();

});

grep.on('exit', function (code) {

if (code !== 0) {

console.log('grep process exited with code ' + code); }

});

When you run the application, you’ll get a listing of all files in the current di-rectory and any subdirectories that contain test in their filename.

CHAPTER 8: Child Processes

The child_process.spawnSync() is a synchronous version of the same function.

child_process.exec and child_process.execFile

In addition to spawning a child process, you can also use child_process.ex-ec() and child_process.execFile() to run a command. The child_pro-cess.exec() method is similar to child_process.spawn() , except that spawn() starts returning a stream as soon as the program executes, as noted in the previous section. The child_process.exec() function, like child_pro-cess.execFile() bufer the results. However, both spawn() and exec() spawn a shell to process the application. In this they difer from child_pro-cess.execFile() , which runs an application in a file, rather than running a command. This makes child_process.execFile() more eficient than ei-ther child_process.spawn() and child_process.exec() .

W I N D O W S F R I E N D L Y

The child_process.execFile() may be more efficient, but child_pro-cess.exec() is Windows friendly, as we’ll see later in the chapter.

The first parameter in the two bufered functions is either the command or the file and its location, depending on which function you choose; the second parameter is options for the command; and the third is a callback function. The callback function takes three arguments: error , stdout , and stderr . The data is bufered to stdout if no error occurs.

If the executable file contains:

!/usr/local/bin/node¶

console.log(global);

the following application prints out the bufered results:

var execfile = require('child_process').execFile,

child;

child = execfile('./app.js', function(error, stdout, stderr) { if (error == null) {

console.log('stdout: ' + stdout);

}

});

child_process.spawn

Which could also be accomplished using child_process.exec() : var exec = require('child_process').exec,

child;

child = exec('./app.js', function(error, stdout, stderr) { if (error) return console.error(error);

console.log('stdout: ' + stdout);

});

The child_process.exec() function takes three parameters: the command, an options object, and a callback. The options object takes several values, includ-ing encoding and the uid (user id) and gid (group identity) of the process. In Chapter 6, I created an application that copies a PNG file and adds a polaroid efect. It uses a child process (spawn) to access ImageMagick, a powerful command-line graphics tool. To run it using child_process.exec() , use the following, which incorporates a command-line argument:

var exec = require('child_process').exec,

child;

child = exec('./polaroid -s phoenix5a.png -f phoenixpolaroid.png', {cwd: 'snaps'}, function(error, stdout, stderr) {

if (error) return console.error(error);

console.log('stdout: ' + stdout);

});

The child_process.execFile() has an additional parameter, an array of command-line options to pass to the application. The equivalent application using this function is:

var execfile = require('child_process').execFile,

child;

child = execfile('./snapshot',

['-s', 'phoenix5a.png', '-f', 'phoenixpolaroid.png'],

{cwd: 'snaps'}, function(error, stdout, stderr) {

if (error) return console.error(error);

console.log('stdout: ' + stdout);

});

Note that the command-line arguments are separated into diferent array el-ements, with the value for each argument following the argument.

CHAPTER 8: Child Processes

There are synchronous versions— child_process.execSync() and child_process.execFileSync() —of both functions. The only diference is, of course, that these functions are synchronous rather than asynchronous. child_process.fork

The last child process method is child_process.fork() . This variation of spawn() is for spawning Node processes.

What sets the child_process.fork() process apart from the others is that there’s an actual communication channel established to the child process. Note, though, that each process requires a whole new instance of V8, which takes both time and memory.

One use of child_process.fork() is to spin of functionality to completely sep-arate Node instances. Let’s say you have a server on one Node instance, and you want to improve performance by integrating a second Node instance an-swering server requests. The Node documentation features just such an exam-ple using a TCP server. Could it also be used to create parallel HTTP servers? Yes, and using a similar approach.

With thanks to Jiale Hu for giving me the idea when I saw his demon-stration of parallel HTTP servers in separate instances. Jiale uses a TCP server to pass on the socket endpoints to two separate child HTTP

servers.

Similar to what is demonstrated in the Node documentation for a master/ child parallel TCP servers, in the master in my demonstration, I create the HTTP server, and then use the child_process.send() function to send the server to the child process.

var cp = require('child_process'),

cp1 = cp.fork('child2.js'),

http = require('http');

var server = http.createServer();

server.on('request', function (req, res) {

res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'});

res.end('handled by parent\n');

});

server.on('listening', function () {

cp1.send('server', server);

});

Running a Child Process Application in Windows

server.listen(3000);

The child process receives the message with the HTTP server via the process object. It listens for the connection event, and when it receives it, triggers the connection event on the child HTTP server, passing to it the socket that forms the connection endpoint.

var http = require('http');

var server = http.createServer(function (req, res) {

res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'});

res.end('handled by child\n');

});

process.on('message', function (msg, httpServer) {

if (msg === 'server') {

httpServer.on('connection', function (socket) {

server.emit('connection', socket);

});

}

});

If you test the application by accessing the domain with the 3000 port, you’ll see that sometimes the parent HTTP server handles the request, and some-times the child server does. If you check for running processes, you’ll see two: one for the parent, one for the child.

N O D E C L U S T E R

The Node Cluster module, which we’ll briefly look at in Chapter 11, is based on the Node child_process.fork() , in addition to other functional-ity.

Running a Child Process Application in Windows Earlier I warned you that child processes that invoke Unix system commands won’t work with Windows, and vice versa. I know this sounds obvious, but not everyone knows that, unlike with JavaScript in browsers, Node applications can behave diferently in diferent environments.

When working in Windows, you either need to use child_process.exec(), which spawns a shell in order to run the application, or you need to invoke whatever command you want to run via the Windows command interpret-er, cmd.exe .

CHAPTER 8: Child Processes

Example 8-2 demonstrates running a Windows command using the latter approach. In the application, Windows cmd.exe is used to create a directory listing, which is then printed out to the console via the data event handler. EXAMPLE 8-2. Running a child process application in Windows

var cmd = require('child_process').spawn('cmd', ['/c', 'dir\n']); cmd.stdout.on('data', function (data) {

console.log('stdout: ' + data);

});

cmd.stderr.on('data', function (data) {

console.log('stderr: ' + data);

});

cmd.on('exit', function (code) {

console.log('child process exited with code ' + code);

});

The /c flag passed as the first argument to cmd.exe instructs it to carry out the command and then terminate. The application doesn’t work without this flag. You especially don’t want to pass in the /K flag, which tells cmd.exe to execute the application and then remain, because then your application won’t terminate.

The equivalent using child_process.exec() is:

var cmd = require('child_process').exec('dir');

Node and ES6 9

Most of the examples in the book use JavaScript that has been widely available for many years. And it’s perfectly acceptable code, as well as very familiar to people who have been coding with the language in a browser environ-ment. One of the advantages to developing in a Node environment, though, is you can use more modern JavaScript, such as ECMAScript 2015 (or ES6, as most people call it), and even later versions, and not have to worry about compatibil-ity with browser or operating system. Many of the new language additions are an inherent part of the Node functionality.

In this chapter, we’re going to take a look at some of the newer JavaScript capabilities that are implemented, by default, with the versions of Node we’re covering in this book. We’ll look at how they can improve a Node application, and we’ll look at the gotchas we need to be aware of when we use the newer functionality.

L I S T I N G O F S U P P O R T E D E S 6 F U N C T I O N A L I T Y

I’m not covering all the ES6 functionality supported in Node, just the currently implemented bits that I’ve seen frequently used in Node appli-cations, modules, and examples. For a list of E6 shipped features, see the Node documentation .

Strict Mode

JavaScript strict mode has been around since ECMAScript 5, but its use directly impacts on the use of ES6 functionality, so I want to take a closer look at it be-fore diving into the ES6 features.

Strict mode is turned on when the following is added to the top of the Node application:

"use strict";

CHAPTER 9: Node and ES6

You can use single or double quotes.

There are other ways to force strict mode on all of the application’s depen-dent modules, such as the --strict_mode flag, or even using a module, but I recommend against this. Forcing strict mode on a module is likely to generate errors, or have unforeseen consequences. Just use it in your application or modules, where you control your code.

Strict mode has significant impacts on your code, including throwing errors if you don’t define a variable before using it, a function parameter can only be declared once, you can’t use a variable in an eval expression on the same lev-el as the eval call, and so on. But the one I want to specifically focus on is this section is you can’t use octal literals in strict mode.

In previous chapters, when setting the permissions for a file, you can’t use an octal literal for the permission:

"use strict";

var fs = require('fs');

fs.open('./new.txt','a+', 0666 , function(err, fd) {

if (err) return console.error(err);

fs.write(fd, 'First line', 'utf-8', function(err,written, str) { if (err) return console.error(err);

var buf = new Buffer(written);

fs.read(fd, buf, 0, written, 0, function (err, bytes, buffer) { if (err) return console.error(err);

console.log(buf.toString('utf8'));

});

});

});

In strict mode, this code generates a syntax error:

fs.open('./new.txt','a+',0666, function(err, fd) {

^^

SyntaxError: Octal literals are not allowed in strict mode. You can convert the octal literal to a safe format by replacing the leading

zero with ’0o'—a zero following by a lowercase ‘o’. The strict mode application works if the file permission is set using 0o666 , rather than 0666 :

fs.open('./new.txt','a+', 0o666 , function(err, fd) {

You can also convert the octal literal to a string, using quotes:

fs.open('./new.txt','a+','0666', function(err, fd) {

let and const

But this syntax is frowned on, so use the previously mentioned format. Strict mode is also necessary in order to use some ES6 extensions. If you

want to use ES6 classes, discussed later in the chapter, you must use strict mode. If you also want to use let , discussed next, you must use strict mode.

D I S C U S S I N G O C T A L L I T E R A L S

If you’re interested in exploring the roots for the octal literal conversion, I recommend reading an ES Discuss thread on the subject, Octal literals have their uses (you Unix haters skip this one) .

let and const

A limitation with JavaScript applications in the past is the inability to declare a variable at the block level. One of the most welcome additions to ES6 has to be the let statement. Using it, we can now declare a variable within a block, and its scope is restricted to that block. Using var , the value of 100 is printed out in the following:

if (true) {

var sum = 100;

}

console.log(sum); // prints out 100

When you use let :

"use strict";

if (true) {

let sum = 100;

}

console.log(sum);

You get a completely diferent result:

ReferenceError: sum is not defined

The application must be in strict mode to use let .

Aside from block-level scoping, let difers from var in that variables de-clared with var are *hoisted to the top of the execution scope before any state-*ments are executed. The following results in undefined printed out with the console, but no runtime error occurs:

CHAPTER 9: Node and ES6

console.log(test);

var test;

While the following code using let results in a runtime ReferenceError stating that test isn’t defined.

"use strict";

console.log(test);

let test;

Should you always use let ? Some programmers say yes, others no. You can also use both and limit the use of var for those variables that need application or function-level scope, and save let for block-level scope, only. Chances are, the coding practices established for your organization will define what you use. Moving on from let , the const statement declares a read-only value refer-ence. If the value is a primitive, it is immutable. If the value is an object, you

can’t assign a new object or primitive, but you can change object properties. In the following, if you try to assign a new value to a const , the assignment

silently fails:

const MY_VAL = 10;

MY_VAL = 100;

console.log(MY_VAL); // prints 10

It’s important to note that const is a value reference. If you assign an array or object to a const , you can change object/array members:

const test = ['one','two','three'];

const test2 = {apples : 1, peaches: 2};

test = test2; //fails

test[0] = test2.peaches;

test2.apples = test[2];

console.log(test); // [ 2, 'two', 'three' ]

console.log(test2); { apples: 'three', peaches: 2 }

Unfortunately, there’s been a significant amount of confusion about const because of the difering behaviors between primitive and object values. Howev-

Arrow Functions

er, if immutability is your ultimate aim, and you’re assigning an object to the const, you can use object.freeze() on the object to provide at least shallow immutability.

I have noticed that the Node documentation shows the use of const when importing modules. While assigning an object to a const can’t prevent it’s prop-erties from being re-used, it can imply a level of semantics that tells another coder, at a glance, that this item won’t be re-assigned a new value later.

M O R E O N C O N S T A N D L A C K O F I M M U T A B I L I T Y

Mathias, a web standards proponent, has a good in-depth discussion on const and immutability.

Like let , const has also block-level scope. Unlike let, it doesn’t require strict mode.

Use let and const in your applications for the same reason you’d use them in the browser, but I haven’t found any additional benefit specific to Node. Some folks report better performance with let and const , others have actual-ly noted a performance decrease. I haven’t found a change at all, but your expe-rience could vary. As I stated earlier, chances are your development team will have requirements as to which to use, and you should defer to these. Arrow Functions

If you look at the Node API documentation, the most frequently used ES6 en-hancement has to be arrow functions . Arrow functions do two things. First, they provide a simplified syntax. For instance, in previous chapters, I used the fol-lowing to create a new HTTP server:

http.createServer(function (req, res) {

res.writeHead(200);

res.write('Hello');

res.end();

}).listen(8124);

Using an arrow function, I can re-write this to:

http.createServer( (req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200);

res.write('Hello');

res.end();

CHAPTER 9: Node and ES6

}).listen(8124);

The reference to the function keyword is removed, and the fat arrow (=>) is used to represent the existence of the anonymous function, passing in the given parameters. The simplification can be extended further. For example, the fol-lowing very familiar function pattern:

var decArray = [23, 255, 122, 5, 16, 99];

var hexArray = decArray.map(function(element) {

return element.toString(16);

});

console.log(hexArray); // ["17", "ff", "7a", "5", "10", "63"] Is simplified to:

var decArray = [23, 255, 122, 5, 16, 99];

var hexArray = decArray.map((element) => element.toString(16)); console.log(hexArray); // ["17", "ff", "7a", "5", "10", "63"] The curly brackets, the return statement, and the function keyword are

all removed, and the functionality is stripped to its minimum.

Arrow functions aren’t only syntax simplifications, they also redefine how this is defined. In JavaScript, before arrow functions, every function defined its own value for this. So in the following example code, instead of my name printing out to the console, I get an undefined:

function NewObj(name) {

this.name = name;

}

NewObj.prototype.doLater = function() {

var self = this;

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(self.name);

}, 1000);

};

var obj = new NewObj('shelley');

obj.doLater();

The reason is this is defined to be the object in the object constructor, but the setTimeout function in the later instance. We get around the problem us-ing another variable, typically self , that could be closed ove r—attached to the

given environment. The following results in expected behavior, with my name printing out:

function NewObj(name) {

this.name = name;

}

NewObj.prototype.doLater = function() {

var self = this;

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(self.name);

}, 1000);

};

var obj = new NewObj('shelley');

obj.doLater();

In an arrow function, this is always set to the value it would normally have within the enclosing context, in this case, the new object:

function NewObj(name) {

this.name = name;

}

NewObj.prototype.doLater = function() {

setTimeout(()=> {

console.log(this.name);

}, 1000);

};

var obj = new NewObj('shelley');

obj.doLater();

W O R K I N G A R O U N D T H E A R R O W F U N C T I O N Q U I R K S

The arrow function does have quirks, such as how do you return an empty object, or where are the arguments. Strongloop has a nice writeup on the arrow functions that discusses the quirks, and the work-arounds.

Classes

JavaScript has now joined its older siblings in support for classes. No more in-teresting twists to emulate class behavior.

How do classes work in a Node context? For one, they only work in strict mode. For another, the results can difer based on whether you’re using Node LTS, or Stable. But more on that later.

CHAPTER 9: Node and ES6

Earlier, in Chapter 3, I created a “class”, InputChecker, using the older syntax: var util = require('util');

var eventEmitter = require('events').EventEmitter;

var fs = require('fs');

exports.InputChecker = InputChecker;

function InputChecker(name, file) {

this.name = name;

this.writeStream = fs.createWriteStream('./' + file + '.txt', {'flags' : 'a',

'encoding' : 'utf8',

'mode' : 0666});

};

util.inherits(InputChecker,eventEmitter);

InputChecker.prototype.check = function check(input) {

var command = input.toString().trim().substr(0,3);

if (command == 'wr:') {

this.emit('write',input.substr(3,input.length));

} else if (command == 'en:') {

this.emit('end');

} else {

this.emit('echo',input);

}

};

I modified it slightly to embed the check() function directly into the object definition. I then converted the result into an ES 6 class.

'use strict';

const util = require('util');

const eventEmitter = require('events').EventEmitter;

const fs = require('fs');

class InputChecker {

constructor(name, file) {

this.name = name;

this.writeStream = fs.createWriteStream('./' + file + '.txt', {'flags' : 'a',

'encoding' : 'utf8',

'mode' : 0o666});

}

check (input) {

var command = input.toString().trim().substr(0,3);

if (command == 'wr:') {

this.emit('write',input.substr(3,input.length));

} else if (command == 'en:') {

this.emit('end');

} else {

this.emit('echo',input);

}

}

};

util.inherits(InputChecker,eventEmitter);

exports.InputChecker = InputChecker;

The application that uses the new *classified (sorry, pun) module is un-*changed:

var InputChecker = require('./class').InputChecker;

// testing new object and event handling

var ic = new InputChecker('Shelley','output');

ic.on('write', function (data) {

this.writeStream.write(data, 'utf8');

});

ic.addListener('echo', function( data) {

console.log(this.name + ' wrote ' + data);

});

ic.on('end', function() {

process.exit();

});

process.stdin.setEncoding('utf8');

process.stdin.on('data', function(input) {

ic.check(input);

});

As the code demonstrates, I did not have to place the application into strict mode in order to use a module that’s defined in strict mode.

I ran the application and that’s when I discovered that the application worked with the Stable release of Node, but not the LTS version. The reason? The util.inherits() functionality assigns properties directly to the object

U S I N G E S 6 F E A T U R E S I N L T S

The issues I ran into with using ES6 features in Node LTS does demon-strate that if your interest is in using ES6 features, you’re probably going to want to stick with the Stable release.

Promises with Bluebird

During the early stages of Node development, the creators debated whether to go with callbacks, or using promises. Callbacks won, which pleased some folk, and disappointed other.

Promises are now part of ES6, and you can certainly use them in your Node applications. However, if you want to use ES6 promises with the Node core functionality, you’ll either need to implement the support from scratch, or you can use a module to provide this support. Though I’ve tried to avoid using third-party modules as much as possible in this book, in this case, I recommend us-ing the module. In this section, we’ll look at using a very popular promises module: Bluebird.

M O R E O N P R O M I S E S A N D I N S T A L L I N G B L U E B I R D

The Mozilla Developer Network has a good section on ES6 promises . In-stall Bluebird using npm: npm install bluebird . Another popular

promise module is Q, but I’m not covering it as it’s undergoing a re-design.

Rather than nested callbacks, ES6 promises feature branching, with success handled by one branch, failure by another. The best way to demonstrate it is by taking a typical Node file system application, and then *promisfying it—convert-*ing the callback structure to promises.

Using native callbacks, the following application opens a file and reads in the contents, makes a modification, and then writes it to another file.

var fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('./apples.txt','utf8', function(err,data) {

if (err) {

console.error(err.stack);

} else {

Promises with Bluebird

var adjData = data.replace(/apple/g,'orange');

fs.writeFile('./oranges.txt', adjData, function(err) { if (err) console.error(err);

});

}

});

Even this simple example shows nesting two levels deep: reading the file in, and then writing the modified content.

Now, we’ll use Bluebird to promisfy the example. In the code, the Bluebird promisifyAll() function is used to promisfy all of the File System functions. Instead of readFile() , we’ll then use readFileAsync() , which is the version of the function that supports promises.

var promise = require('bluebird');

var fs = promise.promisifyAll(require('fs'));

fs.readFileAsync('./apples.txt','utf8')

.then(function(data) {

var adjData = data.replace(/apple/g, 'orange');

return fs.writeFileAsync('./oranges.txt', adjData);

})

.catch(function(error) {

console.error(error);

});

In the example, when the file contents are read, a successful data operation is handled with the then() function. If the operation weren’t successful, the catch() function would handle the error. If the read is successful, the data is modified, and the promisfy version of writeFile() , writeFileAsync( ) is called, writing the data to the file. From the previous nested callback example, we know that writeFile() just returns an error. This error would also be han-dled by the single catch() function.

Though the nested example isn’t large, you can see how much clearer the promise version of the code is. You can also start to see how the nested prob-lem is resolved—especially with only one error handling routine necessary for any number of calls.

What about a more complex example? I modified the previous code to add an additional step to create a new subdirectory to contain the oranges.txt file. In the code, you can see there are now two then() functions. The first pro-cesses the successful response to making the subdirectory, the second creates the new file with the modified data. The new directory is made using the prom-

CHAPTER 9: Node and ES6

isfyed mkdirAsync() function, which is returned at the end of the process. This is the key to making the promises work, because the next then() function is actually attached to the returned function. The modified data is still passed to the promise function where the data is being written. Any errors in either the read file or directory making process are handled by the single catch() .

var promise = require('bluebird');

var fs = promise.promisifyAll(require('fs'));

fs.readFileAsync('./apples.txt','utf8')

.then(function(data) {

var adjData = data.replace(/apple/g, 'orange');

return fs.mkdirAsync('./fruit/');

})

.then(function(adjData) {

return fs.writeFileAsync('./fruit/oranges.txt', adjData); })

.catch(function(error) {

console.error(error);

});

How about handling instances where an array of results is returned, such as when we’re using the File System function readdir() to get the contents of a directory?

That’s where the array handling functions such as map() come in handy. In the following code, the contents of a directory are returned as an array, and each file in that directory is opened, it’s contents modified and written to a comparably named file in another directory. The inner catch() function han-dles errors for reading and writing files, while the outer one handles the direc-tory access.

var promise = require('bluebird');

var fs = promise.promisifyAll(require('fs'));

fs.readdirAsync('./apples/').map(filename => {

fs.readFileAsync('./apples/'+filename,'utf8')

.then(function(data) {

var adjData = data.replace(/apple/g, 'orange');

return fs.writeFileAsync('./oranges/'+filename, adjData); })

.catch(function(error) {

console.error(error);

})

})

.catch(function(error) {

Promises with Bluebird

console.error(error);

})

I’ve only touched on the capability of Bluebird and the very real attraction of using promises in Node. Do take some time to explore the use of both, in addi-tion to the other ES6 features, in your Node applications.

Full-stack Node Development 10 Most of the book focuses on the core modules and functionality that make up Node. I’ve tried to avoid covering third-party modules, primarily because Node is still a very dynamic environment, and support for the third-party modules can change quickly, and drastically.

But I don’t think you can cover Node without at least briefly mentioning the wider context of Node applications, which means you need to be familiar with full stack Node development. This means being familiar with data systems, APIs, client-side development...a whole range of technologies with only one commonality: Node.

The most common form of full-stack development with Node is MEAN—Mon-goDB, Express, AngularJS, and Node. However, full-stack development can en-compass other tools, such as MySQL or Redis for database development, and other client-side frameworks in addition to AngularJS. The use of Express, though, has become ubiquitous. You have to become familiar with Express if you’re going to work with Node.

F U R T H E R E X P L O R A T I O N S O F M E A N

For additional explorations of MEAN, fullstack development, and Ex-press, I recommend Web Development with Node and Express: Leverag-ing the JavaScript Stack, by Ethan Brown; AngularJS: Up and Running, by Shyam Seshadri and Brad Green; the video “Architecture of the MEAN Stack”, by Scott Davis.

The Express Application Framework

In Chapter 5 I covered a small subset of the functionality you need to imple-ment to server a Node application through the web. The task to create a Node web app is daunting, at best. That’s why a application framework like Express has become so popular: it provides most of the functionality with minimal ef-fort.

CHAPTER 10: Full-stack Node Development

Express is almost ubiquitous in the Node world, so you’ll need to become fa-miliar with it. We’re going to look at the most bare bones Express application we can in this chapter, but you will need additional training once you’re finish-ed.

Express provides good documentation, including how to start an applica-tion. We’ll follow the steps the documentation outlines, and then expand on the basic application. To start, create a new subdirectory for the application, and name it whatever you want. Use npm to create a package.json file, using app.js as the entry point for the application. Lastly, install Express, saving it to your dependencies in the package.json file by using the following command:

npm install express --save

The Express documentation contains a minimal Hello World express applica-tion, typed into the app.js file:

var express = require('express');

var app = express();

app.get('/', function (req, res) {

res.send('Hello World!');

});

app.listen(3000, function () {

console.log('Example app listening on port 3000!');

});

The app.get() function handles all GET web requests, passing in the re-quest and response objects we’re familiar with from our work in earlier chap-ters. By convention, Express applications use the abbreviated forms of req and res . These objects have the same functionality as the default request and re-sponse objects, with the addition of new functionality provided by Express. For instance, you can use res.write() and res.end() to respond to the web re-quest, which we’ve used in past chapters, but you can also use res.send() , an Express enhancement, to do the same in one line.

Instead of manually creating the application, we can also use the Express application generator to generate the application skeleton. We’ll use that next, as it provides a more detailed and comprehensive Express application.

First, install the Express application generator globally:

sudo npm install express-generator -g

Next, run the application with the name you want to call your application. For demonstration purposes, I’ll use bookapp :

The Express Application Framework

express bookapp

The Express application generator creates the necessary subdirectories. Change into the bookapp subdirectory and install the dependencies:

npm install

That’s it, you’ve created your first skeleton Express application. You can run it using the following if you’re using a Mac OS or Linux environment:

DEBUG=bookapp:* npm start

And the following in a Windows Command window:

set DEBUG=bookapp:* & npm start

You could also start the application with just npm start , and forgo the de-bugging.

The application is started, and listens for requests on the default Express port of 3000. Accessing the application via the web returns a simple web page with the “Welcome to Express” greeting.

Several subdirectories and files are generated by the application: ├── app.js

├── bin

│ └── www

├── package.json

├── public

│ ├── images

│ ├── javascripts

│ └── stylesheets

│ └── style.css

├── routes

│ ├── index.js

│ └── users.js

└── views

├── error.jade

├── index.jade

└── layout.jade

We’ll get into more detail about many of the components, but the public fac-ing static files are located in the public subdirectory. As you’ll note, the graph-ics and CSS files are placed in this location. The dynamic content template files are located in the views . The routes subdirectory contains the web endpoint applications that listen for web requests, and render web pages.

CHAPTER 10: Full-stack Node Development

The www file in the bin subdirectory is a startup script for the application. It’s a Node file that’s converted into a command-line application. When you look in the generated package.json file, you’ll see it listed as the application’s start script.

{

"name": "bookapp",

"version": "0.0.0",

"private": true,

"scripts": {

"start": "node ./bin/www"

},

"dependencies": {

"body-parser": "~1.13.2",

"cookie-parser": "~1.3.5",

"debug": "~2.2.0",

"express": "~4.13.1",

"jade": "~1.11.0",

"morgan": "~1.6.1",

"serve-favicon": "~2.3.0"

}

}

You install other scripts to test, restart, or otherwise control your applica-tion, in the bin subdirectory.

To begin a more in-depth look at the application we’ll look at the applica-tion’s entry point, the app.js file.

When you open the app.js file, you’re going to see considerably more code than the simple application we looked at earlier. There are several more mod-ules imported, most of which provide the middleware support we’d expect for a web-facing application. The imported modules also include application-specific imports, given under the routes subdirectory:

var express = require('express');

var path = require('path');

var favicon = require('serve-favicon');

var logger = require('morgan');

var cookieParser = require('cookie-parser');

var bodyParser = require('body-parser');

var routes = require('./routes/index');

var users = require('./routes/users');

var app = express();

The modules and their purposes are:

The Express Application Framework

- express - the Express application

- path - Node core module for working with file paths

- serve-favicon - middleware to serve the favicon.ico file from a given path or bufer

- morgon - an HTTP request logger

- cookie-parser - parses cookie header and populates req.cookies • body-parser - provides four diferent types of request body parsers (but

does not handle multipart bodies

Each of the middlware modules works with a vanilla HTTP server, as well as Express.

W H A T I S M I D D L E W A R E ?

It’s the intermediary between the system/operating system/database and the application. The list of middleware that works with Express is quite comprehensive.

The next section of code in app.js mounts the middleware (makes it avail-able in the application) at a given path, via the app.use() function. It also in-cludes code that defines the view engine setup, which I’ll get to in a moment.

// view engine setup

app.set('views', path.join(__dirname, 'views'));

app.set('view engine', 'jade');

// uncomment after placing your favicon in /public

//app.use(favicon(path.join(__dirname, 'public', 'favicon.ico'))); app.use(logger('dev'));

app.use(bodyParser.json());

app.use(bodyParser.urlencoded({ extended: false }));

app.use(cookieParser());

app.use(express.static(path.join(__dirname, 'public'))); The last call to app.use() references one of the few built-in Express middle-

ware, express.static , used to handle all static files. If a web user requests an HTML or JPEG or other static file, express.static is what processes the re-quest. All static files are served relative to the path specified when the middle-ware is mounted, in this case, in the public subdirectory.

Returning to the app.set() function calls, and setting up the view engine, for dynamically generated content you’ll use a template engine that helps map the data to the delivery. One of the most popular, Jade, is integrated by default, but there are others such as Mustache and EJS that can be used just as

CHAPTER 10: Full-stack Node Development

easily. The engine setup defines the subdirectory where the template files (views) are located, and which view engine to use (Jade).

In the views subdirectory, you’ll find three files: error.jade , index.jade , and layout.jade . These will get you started, though you’ll need to provide much more when you start integrating data into the application. The content for the generated index.jade file is given below.

extends layout

block content

h1= title

p Welcome to #{title}

The line that reads extends layout incorporates the Jade syntax from the layout.jade file. You’ll recognize the HTML header (h1) and paragraph (p) ele-ments. The h1 header is assigned the value passed to the template as title, which is also used in the paragraph element. How these values get rendered in the template requires us to return to the app.js file , for the next bit of code:

app.use('/', routes);

app.use('/users', users);

These are the application specific end points, the functionality that re-sponds to client requests. The top-level request ('/') is satisfied by the index.js file in the routes subdirectory, the users, by the users.js file, naturally.

In the index.js file we’re introduced to the Express router, which provides the functionality tor respond to the request. As the Express documentation notes, the router functionality fits the following pattern:

app.METHOD(PATH, HANDLER)

The method is the HTTP method, and Express supports several, including the familiar get, post, put, and delete, as well as the possibly less familiar, merge, search, head, options, and so on. That path is the web path, and the handler is the function that processes the request. In the index.js , the meth-od is get , the path is the application root, and the handler is a callback func-tion passing request and response:

var express = require('express');

var router = express.Router();

/* GET home page. */

router.get('/', function(req, res, next) {

res.render('index', { title: 'Express' });

MongoDB and Redis Database Systems

});

module.exports = router;

Where the data and view meet is in the res.render() function call. The view used is the index.jade file we looked at earlier, and you can see that the value for the title attribute in the template is passed as data to the function. In your copy, try changing “Express” to whatever you’d like, and re-loading the page to see the modification.

The rest of the app.js file is error handling, and I’ll leave that for you to ex-plore on your own. This is a quick and very abbreviated introduction to Express, but hopefully even with this simple example, you’re getting a feel for the struc-ture of an Express application.

I N C O R P O R A T I N G D A T A

I’ll toot my horn and recommend my book, the JavaScript Cookbook, if you want to learn more about incorporating data into an Express applica-tion. Chapter 14 demonstrates extending an existing Express application to incorporate a MongoDB store, as well as incorporating the use of con-trollers, for a full Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture.

MongoDB and Redis Database Systems

In Chapter 7, Example 7-8 featured an application that inserted data into a MySQL database. Though sketchy at first, support for relational databases in Node applications has grown stronger, with robust solutions such as the MySQL driver for Node , and newer modules, such as the Tedious package for SQL Server access in a Microsof Azure environment.

Node applications also have access to several other database systems. In this section I’m going to briefly look at two: MongoDB, which is very popular in Node development, and Redis, a personal favorite of mine.

MongoDB

The most popular database used in Node applications is MongoDB. MongoDB is a document based database. The documents are encoded as BSON, a binary form of JSON, which probably explains its popularity among JavaScript devel-opers. With MongoDB, instead of a table row, you have a BSON document; in-stead of a table, you have a collection.

MongoDB isn’t the only document-centric database. Other popular versions of this type of data store are CouchDB by Apache, SimpleDB by Amazon, Rav-

CHAPTER 10: Full-stack Node Development

enDB, and even the venerable Lotus Notes. There is some Node support of vary-ing degrees for most modern document data stores, but MongoDB and CouchDB have the most.

MongoDB is not a trivial database system, and you’ll need to spend time learning its functionality before incorporating it into your Node applications. When you’re ready, though, you’ll find excellent support for MongoDB in Node via the MongoDB Native NodeJS Driver , and additional, object-oriented sup-port with Mongoose .